Introduction

The World Economic Forum’s Global Cybersecurity Outlook 2026 reinforced that most executives now consider geopolitics to be inseparable from cyber risk. But awareness of geopolitically driven risks is only a first step.

Our Geopolitical Intelligence and Threat Hunting teams collaborate closely to help customers monitor, respond to and mitigate these cyber risks. Although post-incident reports on new APT campaigns and toolsets provide valuable insights, they can often be delayed by months or years after sophisticated attackers gain initial access. To overcome this, we encourage organizations to proactively monitor daily strategic decisions and events that inform a changing threat landscape.

Our approach augments reliance on campaign reports by emphasizing known behaviors and TTPs for detection, threat hunting and mitigation. Tracking subtle changes in the occurrence and intensity of adversarial cyber and information operations across different regions can help identify potential threats based on these groups' known behaviors — e.g., target trends by sector and geography in response to new policies or events.

Mapping these to specific cyber actors’ common tools and tactics can inform realistic scenario planning for stress testing an organization’s cyber risk management framework. It can also help identify opportunities to prioritize pre-built threat hunts aligned to behaviors reused across different APT groups and their affiliated campaigns.

In this report, we outline how insights into global reactions to changing foreign policy can serve as a playbook for defensive strategies against state-affiliated APTs, honing in on key developments in the Indo-Pacific region. Using case studies the Geopolitical Intelligence team illustrates how China deploys its vast cyber resources for strategic, operational and tactical influence. We identify common trends observed from China-linked threat groups participating in Beijing’s hybrid attack efforts, such as Violet Typhoon aka APT 31 and Volt Typhoon, and how they translate to potential impact to regions and sectors.

Key takeaways

- Identifying overlapping adversary tactics and trends can help organizations prioritize detection, threat hunting and mitigation strategies.

- Reviewing immediate reactions to tensions between major economic powers and their respective areas of operation and influence can act as a playbook for mapping potential future cyber threats.

- Adversarial countries’ cyber operatives will continue focusing efforts on aligning with national security-backed state initiatives, which are often outlined in publicly released intelligence reports, yearly budgets and attendance at international summits.

Intelligence predictions: Looking at Beijing’s strategic drivers

Over the past few years, the U.S. rhetoric against China has been increasing in fervor. U.S. President Donald Trump’s return to the White House in January 2025 signaled that Washington would take an even more aggressive stance toward Beijing. Many policies have been created and enacted that restrict the sharing of technology and exporting goods to and from China. Much of this has been done out of national security concerns, as the number of vulnerabilities and backdoors identified in Chinese-made technology goods has increased and been the source of persistent attacks against critical infrastructure globally.

Beijing has not taken the changes lightly. Under President Xi Jinping, it continues to refine its offensive capabilities and take legislative action to ensure its success in the medium-to-long term. In mid-2025, China’s State Council Information Office issued a white paper, “National Security in a New Era”, which framed the country’s strategic priorities for the next decade around national security.

This shift signals China likely will become more confrontational when engaging with countries it perceives to be acting against Beijing’s interests. Beijing's confidence in gaining the upper hand in the event of conflict likely will be bolstered by the success of Chinese APT groups in compromising critical infrastructure worldwide in recent years.

Beijing’s response to key political, military and economic events

| Strategic driver | China’s response |

|---|---|

| U.S. politicians increased anti-China sentiments, calling for enhanced restrictions related to exporting U.S. cutting-edge and emerging technologies. | The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) attempted to seize economic growth under the wire by pilfering U.S. trade secrets before security and trade measures were imposed. |

| The U.S. committed to defending the Philippines and Taiwan if they were attacked by China as it becomes more positioned to be the aggressor in the disputed South China Sea territory. | The CCP showed its effort to cripple U.S. critical infrastructure, which would guarantee widespread panic in the country and distract the U.S. or delay aid from reaching its partners in the Indo-Pacific region. |

| Trump imposed a uniform 10% tariff for all imports, which was followed by “reciprocal” tariffs imposed on dozens of nations. China was the most impacted, with a total effective tariff of 54%. | Beijing declared it no longer was “clinging to illusions” of a deal with the U.S. and retaliated with a 34% tariff on U.S. imports. Japan, South Korea and China also held their first economic dialogue in five years to seek facilitating regional trade — especially on semiconductors and other chip products. |

What Beijing has done

Amid growing tensions over Taiwan’s reunification with China, Beijing has directed its intelligence forces to target Taiwan and leverages its cyber power to pre-posit threat groups deep within essential networks to cause destruction and disruption in the event of conflict. Geopolitical events have been a clear driver for an increase in reported cyberattacks against Taiwan, including the May 2024 inauguration of Taiwanese President Lai Ching-te, who China has branded a “"separatist."

Case study: Cyberattacks against Taiwan

In 2024, Taiwan experienced a daily average of 2.4 million cyberattacks, double the average of the year prior. Chinese state-affiliated hackers mostly used conventional TTPs against Taiwan’s public sector and favored living-off-the-land (LOTL) techniques. Chinese hackers also targeted third-party service providers of internet service providers (ISPs) and the defense supply chain companies to move laterally.

Chinese state-linked cyberattacks against Taiwan’s telecommunications industry rose by 650% in 2024, and attacks against the transportation and defense industries rose by 70% and 57%, respectively. Conversely, attacks against energy, water resources and media entities decreased by 75%, 67% and 18%, respectively. The shift in targeting focus reveals China’s use of offensive cyber methods in alignment with its national strategies. China targeting Taiwan’s telecommunications industry also aligned with its cyber threat activity in the U.S. and other regions.

What Beijing could do

It is possible China would go to great lengths to ensure its strategic position in Asia, specifically Southeast Asia because it sees it as the stabilizing force and hub for explosive growth in the region. The two have deep historical interconnectedness established through centuries of trade and migration. Beijing has leveraged its Belt and Road Initiative, creating a Chinese-centric economy in the Indo-Pacific region.

By leaning more into Southeast Asia as being economically indispensable, China likely seeks to use this position to bend the region to its will. Its reaction to previous geopolitical events impacting the region allows us to curate predictive case studies that assess future actions we would expect to see if Beijing sought to exert its influence to maintain a strategic upperhand.

Case study: Conflict in Southeast Asia

In a hypothetical scenario where China attacks the Indo-Pacific region or a Southeast Asian country, we would likely observe several key maneuvers. Covert influence operations and mobilizing the offensive and defensive capabilities from its private information security vendors would be among the primary characteristics of any such attack. The latter would be tapped to supply malware, tools and access to its collection of information about zero-day vulnerabilities.

Collectively, these strategies aim to give the state-backed cyber threat groups an upper hand when conducting destructive attacks against critical infrastructure. Pre-positioning themselves on the target networks almost certainly will remain a top priority for these groups, who would conduct ruthless and calculated attacks to cause as much damage as possible and induce widespread panic.

Identifying opportunities to hunt APT behaviors

After assessing the strategic elements that drive China’s increased threat posturing and maneuvering, we can look at what’s happening at a tactical level. The strategic knowledge informs us how China may mobilize its offensive capabilities to carry out very specific types of attacks against select entities and sectors in its areas of interest. To operationalize geopolitical intelligence, we can start to look at the specific adversary and the types of attacks they conduct, using insights into behaviors that illuminate opportunities to hunt.

Threat group profiles

The Chinese government drives a large hacking ecosystem in which APT and private companies. We have chosen to highlight Violet Typhoon aka APT31 and Volt Typhoon based on the breadth and scope of their respective operations.

The Violet Typhoon group supposedly is made up of a collection of Chinese intelligence officers, private information security contractors — such as Wuhan Xiaoruizhi Science and Technology Co. aka Wuhan XRZ — and administrative staff that carry out attacks on behalf of the Hubei State Security Department. The group has primarily targeted the U.S., but also Southeast Asia, Hong Kong, Europe and the U.K. in the defense industrial base, information technology (IT), healthcare and energy sectors. Key objectives include stealing diplomatic intelligence and trade secrets and exfiltrating sensitive information about critical infrastructure personnel. These events often coincided with periods of heightened geopolitical tensions between China and the U.S..

The Volt Typhoon group primarily seeks to pre-position itself on critical IT networks for disruption and destruction in the event of conflict with China’s adversaries. This access also can enable the attackers to move laterally to operational technology (OT) assets. The group exhibits only minimal activity within the compromised environments and stays burrowed deep within target networks for years. It has primarily targeted the U.S., particularly the manufacturing, utilities, transportation, government, IT and education industries. The group is considered technically sophisticated and well organized and executes every campaign with intention and in-depth knowledge of its targets. It will attack the same entities repeatedly over extended periods to validate and enhance its unauthorized access.

Trending tactics, capabilities and infrastructure

The transparency in government and private sector reporting of previous campaigns attributed to these groups has played a part in the groups’ emphasis on stealth and changing initial access and persistence tactics. Three tactics stood out.

Exploiting zero-day flaws in edge devices

Edge devices and services such as firewalls and VPN gateways have become popular targets. They are not only internet facing and provide critical services to remote users, but also not easily monitored by network administrators due to a lack of endpoint detection and response (EDR) solutions installed. Several high-profile and high-impact cyberattacks in the past few years were the result of alleged Chinese state-sponsored threat actors and/or groups exploiting flaws in network edge devices. Additionally, it was estimated that 85% of known zero-days Chinese nation-state groups exploited since 2021 were against public-facing appliances.

Living-off-the-land techniques

LOTL techniques use legitimate tools, features and functions available in a target environment to traverse networks and hide within normal network activity. Chinese APTs, including Volt Typhoon, use built-in Windows utilities (wmic, PowerShell, netsh, reg.exe) for stealth, persistence, and lateral movement. China-affiliated threat actor groups have been observed using NetCat shells and modifying the victim registry to enable remote desktop protocol (RDP). Adversaries increasingly use living-off-the-land binaries (LOLBins) such as reg.exe and expand.exe within a batch file on the compromised machine to achieve stealth.

Operational relay box (ORB) networks

ORB networks are global infrastructures of virtual private servers (VPSs) and compromised smart devices and routers. The extensive network of proxy devices allows their administrators to scale up and create a constantly evolving “mesh network” to conceal espionage operations. Each of China’s ORBs is maintained by other private companies or state-sponsored entities and facilitates multiple threat clusters, enabling large-scale, evasive campaigns by proxying traffic through compromised devices. The Violet Typhoon group and several other actors with a China nexus used the FLORAHOX network to proxy traffic from a source and relay it through a Tor network and numerous compromised router nodes to obfuscate the source of the traffic for espionage attacks.

Operationalizing geopolitical insights in proactive threat hunts

Thanks to extensive tagging of hunt packages in the HUNTER library, we’re able to quickly identify a collection of hunts for TTPs known to have been used by Violet Typhoon aka APT31 and Volt Typhoon. Adversaries do evolve TTPs when they become widely detected, but don’t change them as easily or often as indicators of compromise (IOCs), such as IP addresses or file hashes. Tagging allows us to build campaigns consisting of multiple hunts that can be assigned to several analysts in the HUNTER hunt management module and executed concurrently on the organization’s EDR, XDR or SIEM platform. If you'd like to learn more, you can view our on-demand workshop exploring how geopolitical intelligence can strengthen your threat-hunting processes.

We’ve selected nine Volt Typhoon-tagged hunt packages (see below) covering Privilege Escalation. Discovery, Defense Evasion, Execution, Command And Control, Credential Access, and Lateral Movement tactics. The hunt packages are available to HUNTER subscribers, but our team of threat hunters have provided expert tips to isolate data worth pivoting on during an investigation.

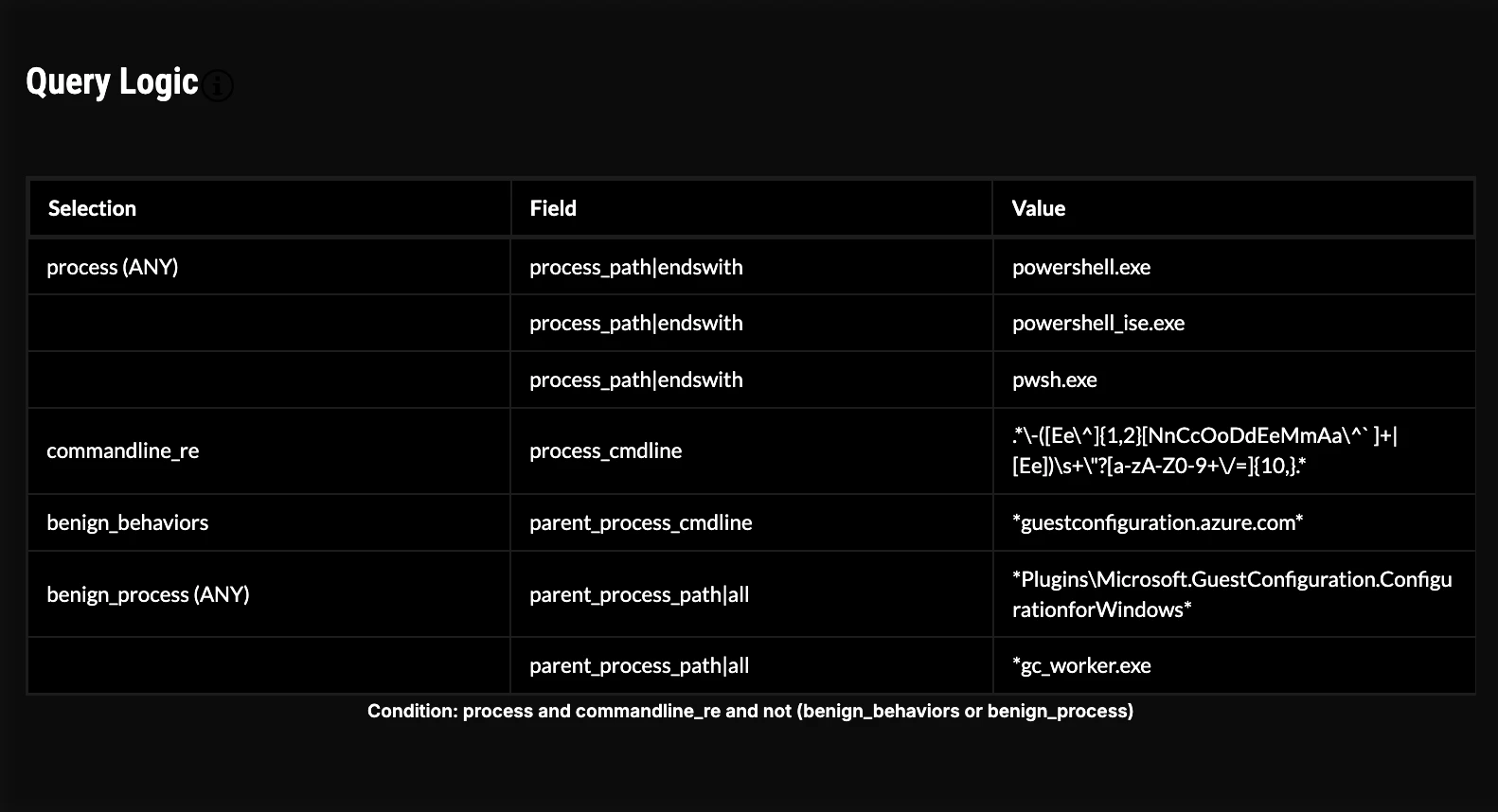

Here we’ll look at the HUNTER package Powershell Encoded Command Execution, which is built to detect widely used defense evasion and execution tactics (Obfuscated Files or Information T1027 and PowerShell T1059.001). This hunt package is a good place to start because it’s easy to capture and the technique is used by many adversaries and malware families. Besides Volt Typhoon, these include APT40, APT42, BlackTech, Charming Kitten, Deep Panda, FIN6, Mango Sandstorm, Mint Sandstorm, Mustang Panda and OilRig.

Looking at the query logic, this hunt query is designed to look for valid variations of the PowerShell -EncodedCommand parameter. Adversaries often use Base64 to obfuscate PowerShell commands, especially with the -EncodedCommand flag, which hides their activities in communications or logs. It has also been used to deliver base64-encoded payloads to obscure malicious instructions from visibility in logs and monitoring tools. It should be noted that not all occurrences will be malicious. For example, benign complex commands may require encoding to properly run on a target system. Threat hunters should analyze the encoded command by base64-decoding the encoded data. Oftentimes adversaries will encode their commands more than once, which makes this technique even easier to identify. Typically, encoded commands are executed with the Execution Policy set to 'bypass'.

Simply identifying the behavior isn’t enough to attribute activity to Volt Typhoon. However, if we’re able to execute and confirm the presence of multiple behaviors associated with Volt Typhoon, the case for attribution to the group becomes much stronger.

Volt Typhoon-tagged HUNTER hunt packages

Pro tip: System/network administrators sometimes use Netsh port forwarding for troubleshooting, lab, or specific support tasks and scheduled scripts or remote management tasks executed under known maintenance windows, often with approved service accounts. Suspicious indicators would be NetSH port forwarding invoked by non-admin users or outside scheduled maintenance periods or abnormal parent processes launching netsh.exe. Also, there may be suspicious command parameters that reference non-standard ports, unknown remote IPs, or using obfuscated command lines/filenames.

Pro tip: Automation, DevOps, or monitoring platforms regularly use encoded PowerShell to circumvent quoting/formatting issues which could make it harder to determine true-positives in a sea of noise. Indicators of true-positives could include encoded payloads with uncharacteristic length, infrequent use, or rapidly recurring in short windows, abnormal processes spawning powershell to execute the encoded command, or common process-chains that may indicate macro enabled documents (e.g. WINWORD.exe spawning powershell) could have played a part in this incident.

Pro tip: IT/admins may remotely launch scripts or software via wmic.exe often during scheduled change windows and under known privileged accounts or may be a part in automation platforms that use WMI for routine software deployment, troubleshooting, or updates. This could all be captured as legitimate activity while process create activity via the “process call create” parameter, or execution by non-administrative or unexpected accounts could indicate suspicious activity. It is recommended to analyze which host was responsible for the remote connection and remote execution as well as determining the user that was responsible for the activity. Is this user operating at a time outside of normal business hours? What was the process that was being created remotely and does this happen regularly in the environment? These are a few questions and HUNTER could ask.

Pro tip: Full AD backups performed by domain administrators as part of an approved, periodic disaster recovery plan may be common activity within an organization and there may also be documented maintenance windows where NTDS database operations are explicitly scheduled and authorized, often with change control tickets, and usually this activity should be conducted by privileged accounts, which could indicate false-positives. This would lead threat hunters to believe that suspicious indicators could contain process command-line arguments matching credential-dumping patterns: `ac`, `ifm`, `c`, `f`, or saving the backups in unusual locations. Something else to keep in mind is suspicious network activity that may surround this activity as it could be an indication of exfiltration.

Pro tip: Legitimate activity would include IT administrators or endpoint management platforms executing WMIC queries as part of health checks, patch audits, or inventory maintenance, WMIC invocation with well-defined, repetitive arguments matching authorized playbooks, or scheduled WMIC scripts running under trusted service accounts during maintenance windows. Suspicious indicators could include WMIC commands with enumeration flags (path, get, list) run by non-admin or non-standard user accounts, anomalous parent processes, or multiple discovery-type WMIC commands from a single host in a short amount of time.

Pro tip: Administrative, monitoring, or deployment tools may use WMI and similar command-line invocations to perform maintenance, push updates, or script configuration. Suspicious activity could include cmd.exe or powershell.exe processes launched via WMI with command-lines showing output redirection (`1>`), quiet/“no prompt” parameters (`/Q`), or script execution (`/c`) or any reference to “ADMIN$” shares. Questions a threat hunter can ask themselves are “Has this ever happened before?”, “Who is the user and does this fit their role?”, and the standard process-chain analysis should be completed to identify any more indicators.

Pro tip: There are very few, if any, legitimate scenarios where non-administrative users or automated scripts run rundll32.exe to invoke comsvcs.dll with the MiniDump function against LSASS, except during highly controlled incident response or memory forensic situations by authorized personnel. Any occurrence of rundll32.exe executing with arguments referencing comsvcs.dll and MiniDump especially if targeting lsass.exe is highly suspect and should be escalated immediately. The process should be checked to determine if this is the true WIndows rundll32.exe, not a process that is masquerading to fool the analyst and root-cause analysis should be conducted. Where did this executable come from or what parent process spawned it should be questions threat hunters ask themselves.

Pro tip: Shadow Copies are routinely accessed or managed by trusted backup software, Windows Restore operations, or during regular system state backups. One approach is to baseline how often this happens and try to identify if this activity lines up with the usual behavior in your environment. Also, keep in mind the process that accessed these Shadow Copies and determine if they are legitimate Windows Operating System utilities. If this is the first time a certain process accessed the ShadowCopies, look at surrounding activity to see what else this process is doing.

Pro Tip: Legitimate activity could include system utilities (e.g., ipconfig.exe, net.exe, tasklist.exe) typically launched by administrators, scripts, or automated management tools via cmd.exe, powershell.exe, or well-known OS services (e.g., WmiPrvSE.exe, Integrator.exe) or certain tools legitimately invoking each other during regular Windows operations. Suspicious activity could include abnormal parent processes that don’t match standard administrative frameworks, binaries known for dual-use or attacker exploitation running outside routine maintenance periods, or child processes stemming from unexpected or low-prevalence parents.

Assessment, outlook

China’s political vision has become more assertive and will continue to shape global discourse, particularly Beijing’s narrative around flash point issues in the APAC region. In the face of tightening security in Western countries, public administration, manufacturing, technology and research entities likely face enhanced scrutiny by their respective governments for suspicious links to Chinese intelligence services. Consequently, entities in Europe and the U.S. likely will experience an elevated level of cyberattacks originating from Chinese threat groups seeking to gain access to confidential information that could have otherwise flowed to Beijing via human intelligence channels.

Separately, APT and hacktivist groups likely will be mobilized to disrupt foreign businesses and public services in retaliation for anything Beijing deems as adversarial conduct. Misinformation and disinformation campaigns powered by AI likely will increase as the Chinese government attempts to discredit Western governments and protect the reputation of the party. Chinese APT groups likely also will conduct highly targeted cyberattacks against individuals and organizations with access to confidential information, as well as posit themselves on the networks of critical infrastructures for destruction or obstruction in the event of escalated conflicts in flash point areas.

Not only will Chinese nation-state threat actors almost certainly continue to pursue high-value targets, it also is probable they will scale up their operations to conduct global campaigns and target as many entities in each region or sector as possible to maximize their gains at every exploitation. The acceleration of improvements in the cybersecurity posture of numerous key targeted countries has compelled Chinese state-sponsored intelligence forces to become more innovative with their attack strategies. China’s intelligence apparatus also has expanded its vulnerability collection capability manifold in the past seven years to maximize the inflow of zero-day vulnerabilities. Similar developments and activity are expected in the next six to 12 months